By The Metric Maven

Bulldog Edition

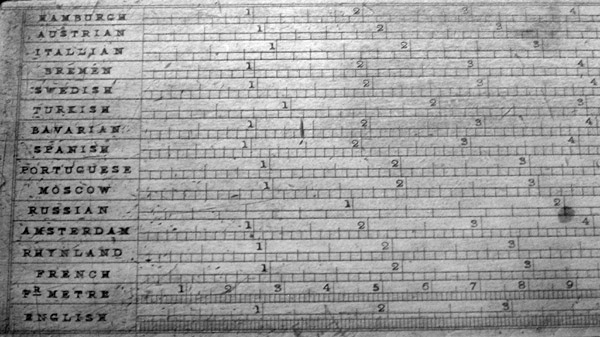

Early in my metric-only odyssey I learned some metric lessons the “hard way.” Because of my inexperience, I had a naïve view of metric implementation that caused me to be incautious. My better half decided she would try using metric for some of her craft work. She flipped her ruler over to its metric side and began using it. I thought nothing of leaving her alone to work, after all metric is simpler—right? Within a few minutes she was complaining that the pattern she was working on was 1.5 mm long and she needed it to be larger. I had seen the pattern and it was way larger than 1.5 mm. Incredulously I walked into her study, looked at the pattern, looked at the ruler and realized it was more like 15 mm in length. I inquired how on earth she measured 1.5 mm, she quickly showed me the marking on the ruler, and I realized that according to the ruler, she was indeed measuring 1.5 mm. Here is the end of that ruler.

One notes that it is labeled millimeters, and therefore one would expect, that like inches, each numbered mark, 1, 2, 3 and so on would be in millimeters! I looked at it in astonishment, and realized that anyone not familiar with the metric system could easily make this mistake. I explained the situation that the large marks are centimeters and the small divisions

are millimeters. It was my first realization that American “Metric” Rulers (AMR) actually had two units, and the imperial side only used inches. Until I actually started using metric exclusively, I had never noticed this. One of my biggest complaints is the common mixing of units in imperial. For instance a person’s height might be 1 yard, 2 feet, 10 inches and 1 barleycorn tall. Ok, we have simplified this to just 5′ 10 1/3″ but that’s still two units–designated with quotation marks. The use of multiple units is a clear violation of Naughtin’s Laws and only serve to obfuscate the experience of a direct cognitive understanding of magnitude.

I realized that the ruler should say cm instead of mm. This caused me to start looking at rulers offered in office supply stores. It is there, one can see that the metric side of a dual-scale ruler gets little respect. For instance, I went to an office supply store recently and purchased a green ruler, fabricated by a company which boasts they have made rulers since 1872. You can see that the designation is cm this time, but the origin of the scale is on the end which is rounded and used to hang the ruler on a wall. The inch side gets the square end which is psychologically more appealing. You don’t think this is a big deal? When you pick up a slice of pizza, how often do you begin eating the wide, crusted end?—rather than starting with the point? Simple ergonomics matter.

But in reality, both millimeters and centimeters exist on this ruler. To my surprise, the store brand rulers have both mm and cm designated at the end. Someone actually thought about this and marked both! Unfortunately, it now gives one two possibilities for what the numerical marks might designate, instead of resolving the situation. Assuming one knows which are cm and mm, a person can, for example, measure something with an American “Metric” Ruler, which is say 1.5 cm long. So how is this done? One first looks at the 1 cm designation, then counts the millimeters, and concatenates them with a decimal point to obtain the answer. You are always holding the first digit in your mind 1 and then counting to the next digit, which is 5 and then creating the answer of 1.5 cm. This is true even if you designate the millimeter graduations as tenths of centimeters. When I first received an Australian metric ruler, it had nothing but millimeters, and my mind quickly responded to its ease of use. The Australian who sent it to me said “I learned early on that centimeters cause mistakes, and in my business this cost me money, and I stopped using them.” He told me it took Australians a while to realize this, but more and more, he was seeing centimeters, less and less.

In my engineering work, I have never seen a metric drawing in centimeters. After I had used a metric ruler marked only in millimeters, I hoped I would never encounter one. A client who is an imperial die-hard informed me that there is no use using metric, you have to buy meat in pounds, and lengths in yards, or feet or inches in this country. I was told to “get real.” My reaction to his statement was not what I expected, my mind wandered back to my youth, when lumber yards, car dealers and others would hand out free yardsticks on the Fourth of July, Labor Day and on other important dates for advertising. I realized that I needed to hand out mm only rulers to my clients, as I suspected many of my clients, despite all being engineering firms, had never seen such a thing as a mm ruler. I first tried to get wooden millimeter rulers from wooden yardstick suppliers. One of the vendors informed me, in no uncertain terms, that this is America and we use inches. Finally I came across a supplier who would make custom metal mm-only rulers for me. I decided to go with a 600 mm long ruler to hand out to my clients and their Engineers. I reasoned 600 mm would be long enough to measure most common designs found in my industry, which is microwave and antennas. The rulers are metric-only (no inches), have my company logo, name and information, just like the old wooden ones, which are now collected as antiques. The end of one of my mm-only metric rulers is shown in the inset above.

When I handed out the mm-only rulers, I was pleasantly surprised by the reactions. One Engineer said “Oh, thank heaven’s it’s 600 mm, that’s actually a useful length.” Two others at another company took the opportunity to thank me for suggesting the centimeter be eschewed, they really found it simplified matters. One older Engineer said “It’s amazing, I’m starting to lose my feel for inches, and think in millimeters now. This ruler is great.” I was floored. I was used to a much more visceral and negative reaction, or one of dismissive semi-contempt. I later had lunch with two Engineers, one of which has seemed to enjoy his attempts at devil’s advocate for centimeters. He continued trying to needle me, and then quickly moved the ruler I’d given him closer to his person, and said “Now you aren’t thinking of taking this back—are you?” I replied “I can see that a ruler like this desperately needs to be with someone like you.” When I took a ruler to the Engineer who had told me to “get real,” his countenance was that of a person who had asked me to find a Unicorn, and I had obtained one, broke and saddled it for his riding pleasure, then delivered it to his door.

This is the first time, that I felt I might have made a small difference in American metrication, but why was this time different? My conclusion is the ubiquitous presence of American “Metric” Rulers. They offer very little obvious advantage, and probably are viewed as an equivalent to decimalized inches, or are seen as even more complicated with their mixture of cm and mm scales. I’ve come to believe more and more that American “Metric” Rulers are a big obstacle to Americans adopting metric for common everyday use. With millimeters, one almost never needs a decimal point for common measurements, but this simplicity is never experienced, or realized, because all that is around us are American “Metric” Rulers. A small step which might help metrication in this country, would be to mandate that ruler manufacturers change the “metric” side of our dual-scale rulers to millimeter only. It’s a minute change, but I think it might cause people to view the metric system more favorably, and even possibly use that side of the ruler more often. Dual scales (mm and inches) clearly violate Naughtin’s Laws, and conspire to put off metric use, but it would be some small victory toward mandatory metrication.

I have wondered many times since, that if, many years ago, I had attended local Fairs in the Midwest, where the metric side of the wooden yardsticks was in millimeters, if we might not be much further down the path to metrication, and not continuing to stand still as we have been for over 150 years.

Related essays:

If you liked this essay and wish to support the work of The Metric Maven, please visit his Patreon Page and contribute. Also purchase his books about the metric system:

The first book is titled: Our Crumbling Invisible Infrastructure. It is a succinct set of essays that explain why the absence of the metric system in the US is detrimental to our personal heath and our economy. These essays are separately available for free on my website, but the book has them all in one place in print. The book may be purchased from Amazon here.

The second book is titled The Dimensions of the Cosmos. It takes the metric prefixes from yotta to Yocto and uses each metric prefix to describe a metric world. The book has a considerable number of color images to compliment the prose. It has been receiving good reviews. I think would be a great reference for US science teachers. It has a considerable number of scientific factoids and anecdotes that I believe would be of considerable educational use. It is available from Amazon here.

The third book is not of direct importance to metric education. It is called Death By A Thousand Cuts, A Secret History of the Metric System in The United States. This monograph explains how we have been unable to legally deal with weights and measures in the United States from George Washington, to our current day. This book is also available on Amazon here.