By The Metric Maven

Bulldog Edition

The skeptic does not mean he who doubts, but he who investigates or researches, as opposed to he who asserts and thinks that he has found.

– Miguel de Unamuno

For many years I had been directly involved in scientific skepticism, which is often found under the rubric of “skeptics” these days. The organization for which I volunteered was disbanded a number of years back. It was this vacuum of spare time which allowed me to return to my interest in the promotion of the metric system. I had not thought about the Skeptics much for a number of years until my friend Kat, and another long-time Skeptics friend Ollie suggested I listen to the Skeptics Guide To The Universe podcast.

I was surprised at how interesting I found the program, and I began to listen to it regularly. Then a few notes of measurement discord surfaced. I used their online form to request they stick with metric and also most definitely stop quoting inches and centimeters and go with millimeters exclusively for a small metric unit. I linked to a number of my essays on the subject of millimeters versus centimeters.

I have emailed other programs, podcasts and such, and generally encounter silence. I was rather surprised when it appeared that someone actually read my online form submission (as I don’t have a copy I can’t review what I actually said).

Their podcast Episode #486 2014-11-08 actually acknowledged my submission. The subject under consideration was the Fanged Deer (25:53), here is my own attempt at a transcription:

Steve: Evan, I’m looking at a very cool picture of a vampire deer. Or something like that—tell me about this.

Evan: Uh Vampire deer, yeah well—well Steve and folks I’m sure you’ve heard of let’s say the white tailed deer. Right? we’ve all heard of that pretty common. We’ve probably heard of the Red Deer maybe, or you’ve even heard of a Reindeer, and you even heard “do” a deer at some point in your life.

Steve: Buck (?)

Evan: But—but I defy the SU listener to have ever heard of a Kashmir Musk Deer at least prior to recent news headlines. Uh and because you have probably never heard of this species of deer before and-there whose official taxonomical designation is Moschus cupreus it’s a one of seven Moschidae species found in Asia. Um, this Kashmir Musk Deer is uh in fact quite an interesting animal in that the males of the species grow tusks and the tusks can grow as long as ten centimeters—or rather what is that a hundred millimeters—because someone told us recently that centimeter measurements is rubbish—who is it who that said that?.

Steve: Yeah, some metric fanatic. [laughing]

Evan: Yeah–that’s right [laughter]

Steve: Yeah, he made a reasonable argument but it was his point was that centimeters are confusing and the only reason people only use them because they’re sort of inches but [laughter] for conversion purposes just sticking with millimeters is less confusion.

Evan: Right—so a hundred millimeters let’s call it.

Steve: Allright.

Evan: And of course what with Halloween just recently cominal(?) they’re being called in the news as vampire deer.

I was chagrined to be called a metric fanatic, which appeared to have been in a rather haughty and dismissive manner. I emailed SGU and also pointed out that I had been involved with scientific skepticism for many years before I began my metric quest.

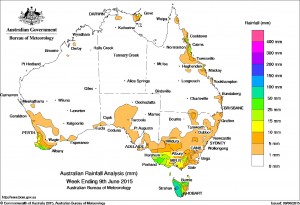

The SU group then took a trip to Australia, which I hoped might actually cause them to notice they were in a metric country which speaks English. They also visited New Zealand, and did not seem to find it novel to order steaks in grams and drinks in milliliters. Perhaps they didn’t eat or drink while they were there? It will probably not come as a surprise to my readers that the mention of millimeters on the SU podcast was fleeting, and an examination of clear metric usage by the panel of scientific communicators was apparently of little interest.

The podcast has continued to use centimeters, inches, microns, and whatever units are the path of least intellectual resistance for their segments. I have emailed them about numerical presentation, but now I’m just dismissed as “some metric fanatic”—like a follower of Eric Von Daniken, Charles Berlitz, Uri Geller, Jenny McCarthy. or Charles Piazzi Smyth. I found it strange that the same manner of dismissive attitude which paranormal enthusiasts have used to dismiss scientific skeptics was employed by SGU toward me. It’s strange to see these promoters of science taking the same line toward the metric system as John Bemelmans Marciano does in his recent celebration of failure.

The phrase critical thinking is generally employed by Skeptics to describe what they are promoting and what they do. Skeptics also assert they are promoting science. Critical thinking relies on informing oneself about a subject and evaluating available information. It appears that when it comes to the metric system, the panelists of the Skeptics Guide to The Universe (SGU) apparently have already decided that the matter of a measurement policy for their show is trivial. They’ve already learned all they need to know by osmosis and so it requires no examination, investigation or self-education.

Steven Novella (Steve in the dialog above) has produced a video for The Great Courses, which has also been promoted on the SGU program. Its title is Your Deceptive Mind: A Scientific Guide to Critical Thinking Skills. One of the subjects examined in the video (which I don’t have, nor have I seen) according to Steven Novella is innumeracy. A person who claims expertise in numeracy and laughs when questioned about the most intuitive use of the metric system for numerical presentation? Wow, I don’t know what to say. I cannot not even construct a sentence in response.

I would suggest Steve Novella consider looking at some of my essays for some numerical guidance. My essay One Hundred is Everywhere delves into fuel efficiency and how it might best be expressed in liters per 100 Kilometers rather than Kilometers per liter. That seems like a reasonable topic for discussion. I address the poor expression of numerical information in my review of the book The Story of Measurement. Other relevant essays on numerical presentation are: Joule in the Crown, Technical Presentation and Metric, A Kilotonne is How Much in Metric?, American Software vs Metric, Feral Units Endanger Our Health, and Don’t Get Engaged with Gauge.

In my emails to SGU, I provided a number of links to what I believe to have been important basic metric articles I’ve written and linked to Naughtin’s Laws. I pointed out to SGU that if they did not believe me, they should look at what Pat Naughtin left behind—in his videos and writing. I included links to Pat’s works. Perhaps they might even look at the monograph Metrication in Australia?—to help them with any critical thinking they might like to do with respect to the most effective use of the metric system for technical presentation. Perhaps The Skeptics Guide To The Universe might even question—as I have-–how astronomers present distances.

The catch phrase “science communicator” has commonly been invoked in recent SGU broadcasts. This appears to be an expertise they claim to possess. It appears to me, that to communicate science, one should examine how numerical information is best presented, and what the clearest format one might use to provide intuitive numerical information might be. Have they investigated Pat Naughtin’s whole number rule? Have the SGU members thought about the use of metric prefixes to make astronomical distances more understandable to everyone? Could it be that using the light year is just an obfuscating gee-whiz! unit that does not provide context?—of course not, no critical thinking needed there—case closed. How about examining the history of the metric system for unnecessary 19th century? baggage—for example the demi-dekagram and demi-deciliter. Have they ever wondered why chemists don’t use centiliters, or deciliters, but do use milliliters?

I’ve discovered that numerical values are not used on SGU nearly as often as one might think, but when they are, they are not optimum in my view. Here are some of the numerical presentations I’ve found rather cringe-worthy:

SGU on 2015-02-02

During a discussion of the close approach of asteroid 2004 BL86 it was stated that it was within 745,000 miles or 1.2 million Kilometers. They then state that this is 3.1 times the distance from the Earth to the moon. There is a useful metric prefix Mega, to describe this nearest asteroid distance; which would make it 1200 Megameters. The distance of the Earth from our moon is 384 Megameters. The relative magnitudes are rather clear when one uses integers and an appropriate metric prefix.

During a discussion of the size of wormholes it was stated that theoretical values range down to 10-33 centimeters. The range of metric prefixes goes down to yocto which is 10-24 meters. The values are clearly outside of the range of metric prefixes. Why on Earth would centimeters be used as a base unit?—particularly in scientific notation. Does it add anything other than a comforting bit of non-information? How about 10-35 meters? How small is this? Well the linear cross-section of lower energy neutrinos is thought to be somewhere around 20 yoctometers which is 20 x 10-24 meters. The smallest wormhole is about 100 000 000 000 or 100 billion times smaller than the realm of a neutrino, or 100 Megatimes smaller. Why the centimeters?—are they being passive aggressive?—or sloppy?

SGU on 2015-03-21

While describing the computer cluster that will be used with the Large Hadron Collider, petabytes, gigabytes and one participants favorite, yottabytes, were used. When metric prefixes are received wisdom, they are employed without critical regard.

SGU on 2015-04-07

It was noted that global warming/climate change had increased the amount of vegetation on Earth such that 4 billion tons of carbon had been sequestered, but 60 billion tons of carbon were released over the same period. [It isn’t clear from the audio if they mean tons or tonnes] These values are about 4 Petagrams and 60 Petagrams respectively. Oil production worldwide each year is on the order of 4 Petagrams, and the total amount of carbon in the Earth’s atmosphere is approximately 720 Petagrams. There was no attempt to use metric in this segment of the show, but as soon as computer storage was broached, Terabytes and such quickly appeared.

Then this strange exchange occurred on 2015-04-18. The “science communicators” discuss the innate fear of spiders that most humans possess. Then the SGU members introduce some “scientific levity.” I have been unable to separate out the voices:

“I believe that we’ve all seen an example of the purple recluse spider.”

“Ah yes, It has a bow tie shape on it’s neck region.”

“They live in dark tunnels, they do, and uh they’re bottom feeders essentially [laughter]…..and, and, and they absolutely adore the metric system, from what I hear.

“They only move in millimeters. It’s weird.”

I have no idea if this statement is aimed at your friendly neighborhood Metric Maven and his purple masthead, but I find the shot at the metric system by “science communicators” sad, and if its aim was wider than that, then I suggest these “science communicators” read up on the definition of ad hominem attack. It may be my sensitivity, but there were then a number of centimeters thrown in, seemingly with emphasis, for “good measure.” Well, correlation does not necessarily imply causality. I could be experiencing confirmation bias. It is a strange set of “science communicators” who take the metric system as a source of amusement. Apparently they cannot be bothered to investigate the metric system, or at a minimum watch Pat Naughtin’s Google video.

SGU on 2015-04-25

During a discussion of the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) this exchange occurred:

Brian Wecht: “I wrote this down let me check yeah—was up to 4 Tev—Teraelectron-volts ok, which is just some unit of energy that’s a lot it, it was a record setting beam, when they turned it on, and some of that energy in the beam right the protons collide and annihilate…..”

Steve Novella: “Let’s put this into a frame that people understand—how quickly would that pop a jiffy pop popcorn?

Brian Wecht: Super fast dude!—crazy fast

Person 1: “Mega” [talking over one another] “in an attosecond.”

[talking over one another]

Later in the conversation:

Brian Wecht: “…..”They got up to 6.5 Tev”

And Later, after a discussion of the possibility of the LHC creating a black hole was discussed, this was said:

Person 2: “We could go now two years, three years of these 14 Terawatt beams smashing into each other and we could see nothing…”

An electron-volt (ev) is equivalent to 1.6×10−19 joules (160 zJ). A Teraelectron-volt is therefore 160 nanojoules. How much energy is in a joule? If one has a small apple, which is about 100 grams and it is dropped from the height of a doorknob (about 1 meter), the energy it has when it strikes the floor is approximately a joule. A Teraelectron-volt is 6 125 000 times smaller than the amount of energy the apple possesses when it hits the floor after dropping from the height of a door handle. This is a tiny amount of energy, and a Tera-ble use of the prefix Tera.

The answer as to how long it would take to pop a jiffy pop popcorn is—-infinity. I suspect a Teraelectron-volt is more akin to the energy of a metaphorical butterfly sneeze. It could not pop a single kernel of popcorn—nor could 6.5 Tev—which is 1040 nanojoules. Wikipedia states that the kinetic energy of a flying mosquito is about 160 nanojoules. Not a single kernel of popcorn will be exploded when absorbing a Teraelectron-volt of energy, nor would a flying mosquito probably possess the energy to produce a black-hole I suspect. A Tev may be a large amount of energy for a subatomic particle, and its interactions, but on the macroscopic level, it’s infinitesimal.

A garden variety micrometeorite has a mass of about 50 micrograms, and travels at a velocity of about 10 Kilometers per second. The kinetic energy of this example micrometeor is 15.63×1018 electron-volts or 15.63 Exaelectron-volts or 15.63 Eev. This kinetic energy value is two metric prefixes larger in magnitude (1 000 000) than the 6.5 Tev quoted in SGU for subatomic particles—this garden variety micrometorite has far more energy than the LHC imparts to subatomic particles. In everyday terms the energy in the example micrometeor is 2.5 joules.

I’m unable to identify Person 2. I have no idea where the 14 Terawatt value originated, but watts are units of power. Power, for us “metric fanatics,” is a joule per second. In one second this would be 14 000 000 000 000 joules of energy or 14 Terajoules. For reference the atomic bomb which exploded over Hiroshima released about 63 Terajoules of energy. It is probable that this was just a quick mistake during the rapid fire exchanges, but it is a big one. The other “Science Communicators” should have possibly taken note, but did not. They were too busy making science “fun.”

SGU on 2015-05-23

The SGU members describe a new beam splitter for light which is much smaller than previous designs, and assert that it’s a great breakthrough for photonic computing (later in their farrago of talk they seem to question this assertion). SGU’s discussion of photonic computing is so muddled and painful to listen to, that I have not attempted to make a transcript and my comments would constitute another essay entirely. Jay states: “…photonic computing: it uses photons in the visible or infrared light spectrum….” Perhaps at this point they might have pointed out that light waves in the visible spectrum have wavelengths in the nanometer range, say about 500 nanometers or so (or 500 millimicrons to stay SGU-inconsistent). The SGU interlocutors quote current beam splitters as being about 100 by 100 microns, and the new beam splitter is about 2.4 by 2.4 microns. They use the non-descriptive term micron for micrometers. The use of microns only serves to obfuscate and does not provide magnitude context or information.

Jay then states:

Jay: And to give you an idea about how small this is, its about one-fiftieth of a human hair—so it’s not even visible.

Bob: An angel can’t even dance on the tip of it.

I very much like comparisons of this type, but a context with light would be useful. A human hair has considerable variation (17-181 μm), but one can say it’s about 100 micrometers in diameter as an overall estimate. The current beam splitter design has about the same cross-section as a hair. The new beam-splitter is about 3 x 3 micrometers. But what about light? The size of the baseline beam splitter is originally 100 000 x 100 000 nanometers, it is now 2400 x 2400 nanometers. A representative wavelength of visible light is on the order of 500 nanometers. This is why one can’t go much smaller and still illuminate the beam splitter, and still have it operate as a beam splitter. The members of the SGU apparently can’t bring themselves to do something other than just parrot back microns, as they probably read in the media, and continue to propagate poor measurement exposition without a second thought. Pun intended.

• • •

This scientific blind-spot, that these “scientific communicators” have for using the metric system carelessly, is not unique to SGU, it exists in all of engineering and science. If you sense my frustration, it is because a tool is being misused, and being subjected to sanctimonious dismissal by “scientific professionals,” “scientific communicators,” and others at SGU. If The Skeptic’s Guide to The Universe were Fate magazine, I would not bother to point out its faults, but I’ve been on the side of scientific skepticism all of my life. Since I began to listen to the SGU podcast, I don’t recall any of the regulars ever expressing remorse or concern that the US does not use the metric system. They managed to visit Australia and not note the use of the metric system in almost every aspect of everyday life. I find it vexing and dispiriting when people that represent a group I once spent so much of my volunteer time with promoting science, greets the metric system with the same indifference as those who don’t claim to have any expertise in science whatsoever, and then call themselves skeptics. E tu Skepti?

If you liked this essay and wish to support the work of The Metric Maven, please visit his Patreon Page and contribute. Also purchase his books about the metric system:

The first book is titled: Our Crumbling Invisible Infrastructure. It is a succinct set of essays that explain why the absence of the metric system in the US is detrimental to our personal heath and our economy. These essays are separately available for free on my website, but the book has them all in one place in print. The book may be purchased from Amazon here.

The second book is titled The Dimensions of the Cosmos. It takes the metric prefixes from yotta to Yocto and uses each metric prefix to describe a metric world. The book has a considerable number of color images to compliment the prose. It has been receiving good reviews. I think would be a great reference for US science teachers. It has a considerable number of scientific factoids and anecdotes that I believe would be of considerable educational use. It is available from Amazon here.

The third book is called Death By A Thousand Cuts, A Secret History of the Metric System in The United States. This monograph explains how we have been unable to legally deal with weights and measures in the United States from George Washington, to our current day. This book is also available on Amazon here.