By The Metric Maven

One evening over the phone, my friend Lapin told me that he spent the weekend with another Engineer, Mr. Landi, building a shed. Mr. Landi suggested they build it using metric so it would be more accurate. Apparently this exercise in construction went down hill immediately. “We made all kinds of mistakes cutting lengths.” Lapin said exasperated. I then asked a question which took Lapin by surprise:

“Did you build it using centimeters or millimeters?”

“It makes a difference?” Lapin inquired with incredulity.

“Yes, you’re prone to make numerous errors when you use centimeters. Millimeters eliminate a major source of those errors, by eliminating the decimal point.”

I explained that in Australia, nothing but millimeters are used for their building construction. The numbers are all simple integers, and no addition or subtraction with decimal points are needed. The least numerate of the workers can use a calculator to add and subtract integers with ease and accuracy. It’s saved Australia about 10-15% on the cost of construction since their metric conversion in the 1970s, when compared with imperial.

It was hard to fault Lapin or Mr. Landi for not using millimeters. In the US, obtaining a decent metric tape measure, or other construction tools in millimeters, is almost impossible, because of The Invisible Metric Embargo.

The formal recommendations for metric construction in the United States is in the Metric Design Guide (PBS-PQ260) September 1995. Here is what it has to say about the use of centimeters in construction:

Centimeters (cm)

Centimeters are typically not used in U.S. specifications. This is consistent with the

recommendations of AIA and the American Society of Testing Materials (ASTM).

Centimeters are not used in major codes.

Use of centimeters leads to extensive usage of decimal points and confusion to new readers. Whole millimeters are being used for specification measurements, unless extreme precision is being indicated. A credit card is about 1 mm thick.

Here is the Guide’s statement about millimeters:

Millimeters (mm)

SI specifications have used mm for almost all measurements, even large ones. Use of mm is consistent with dimensions in major codes, such as the National Building Code (Building Officials and Code Administrators International, Inc.) and the National Electric Code (National Fire Protection Association).

Use of mm leads to integers for all building dimensions and nearly all building product

dimensions, so use of the decimal point is almost completely eliminated. Even if some large dimensions seem to have many digits there still will usually be fewer pencil or CAD strokes than conventional English Dimensioning

A Canadian building construction guide has nice illustrations of the difference—which are absent in the US guide. Unfortunately, Canada’s building trades have not converted to metric, which is why I generally discuss the Australians instead. I have not been able to locate Australian building guides. This is why you will find none in this blog.

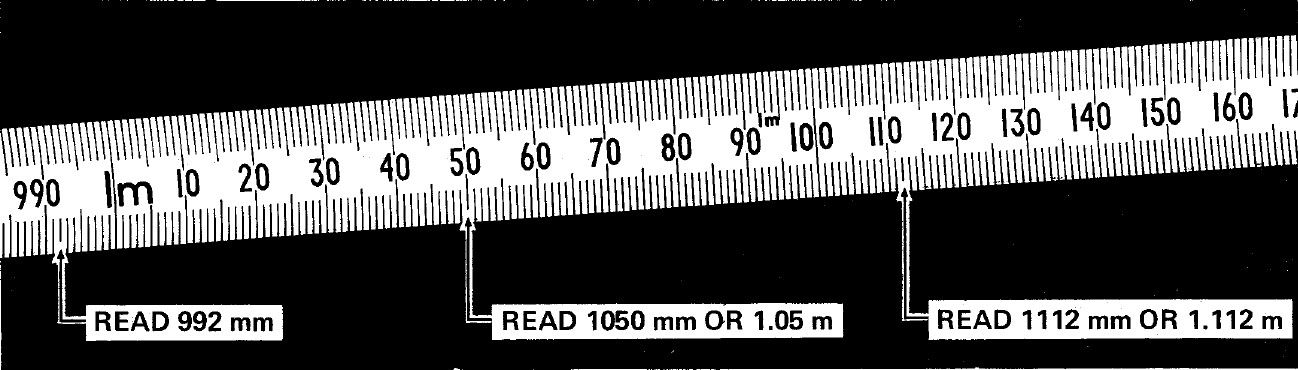

The Canadian guide shows how to read a metric tape measure. This tape measure has two units on it meters and millimeters. You can compare it with an Australian tape measure I own below. It remains all millimeters, but only counts off the 100 mm between without the largest digits.

Next the Canadian guide shows a typical wall dimensioned with imperial units.

It never strikes Americans as excessive to use two units to describe every dimension. Feet and inches are found everywhere, along with fractions.

The same wall is then presented as it would be dimensioned and drawn using millimeters. The numbers are all simple integers.

No Feet and inches, no fractions, no decimal points, and just one unit used for all sizes. The dimensions are easy for a novice or experienced builder to read clearly. Experience in Australia shows that workers will attempt to cut to the exact millimeter when given tools with that capability. We would have more accurately constructed buildings, which are more weather-tight, simply by switching to metric.

Pat Naughtin relates that the head of AVJennings construction in Australia had two identical houses constructed, one in imperial and one in metric. It took two large trucks to haul away the scrap from the imperial work site. The metric house work site had only about a wheelbarrow full. When reformed in a rational up-to-date manner, metric can provide easy dimension checks. Pat relates that Australian bricks are 90 mm thick, and are specified to have 10 mm of “mud” between them. This means that if you have ten rows of bricks laid down, they should measure exactly one meter. Imperial units simply do not accommodate this manner of easy check.

One owner of an Australian construction company has a blog entry with a title which is succinct concerning our American building practices: Why not going Metric makes America a laughing stock. He concludes his blog entry thus:

One of the last hold outs in a the push toward metric is the American building industry. The lure of inches for lumber and lengths in feet is seemingly irresistible. (it is even curious that the Americans call that timber a 2X4, where in Australia it was a 4X2) To avoid the confusion…… the Australian building industry declared.

The metric units for linear measurement in building and construction will be the metre (m) and the millimetre (mm), ….. This will apply to all sectors of the industry, and the centimetre (cm) shall not be used.’

We banished the centimetre as some defacto inch measurement and have never looked back.

It speaks volumes about the US that they believe in some unalienable right to an outdated, and uniquely strange system of measures in this current millennium.

Related essay:

If you liked this essay and wish to support the work of The Metric Maven, please visit his Patreon Page and contribute. Also purchase his books about the metric system:

The first book is titled: Our Crumbling Invisible Infrastructure. It is a succinct set of essays that explain why the absence of the metric system in the US is detrimental to our personal heath and our economy. These essays are separately available for free on my website, but the book has them all in one place in print. The book may be purchased from Amazon here.

The second book is titled The Dimensions of the Cosmos. It takes the metric prefixes from yotta to Yocto and uses each metric prefix to describe a metric world. The book has a considerable number of color images to compliment the prose. It has been receiving good reviews. I think would be a great reference for US science teachers. It has a considerable number of scientific factoids and anecdotes that I believe would be of considerable educational use. It is available from Amazon here.

The third book is not of direct importance to metric education. It is called Death By A Thousand Cuts, A Secret History of the Metric System in The United States. This monograph explains how we have been unable to legally deal with weights and measures in the United States from George Washington, to our current day. This book is also available on Amazon here.