By The Metric Maven

Bulldog Edition

I have a friend, Pierre, who has a passion for woodworking, but a passion for metric?—not so much. My knowledge of woodworking is at best minimal, but Pierre does his best to enlighten me. One evening I received an email from him after he had watched a woodworking program by Roy Underhill. Roy is an American, and a bit of legend in woodworking as I understand it. During the program, Roy explained a Swedish method of teaching called sloyd. My friend Pierre then related:

The original Swedish drawings in the book of exercises he used were measured in metric. Underhill says, “I took up woodworking so I wouldn’t have to learn metric.” Thought you’d want to know that.

Next, Underhill was showing how to measure 2 cm over on a board using a Swedish wooden folding rule. He said he got it from some visiting Swedish woodworking friends, because his American one doesn’t have centimeters on the back. He said, they said, and this is really the part I wanted you to know, that in Sweden, his woodworking friends use only inches.

Then, he flipped the Swedish folding rule over, and it showed inches. Here’s another interesting part, I hope you aren’t asleep yet.

The Swedish “inch” is bigger than our inch. Holding the rules one over the other, you could clearly see the Swedish “inch” is about 1/16 bigger.

WTF, man?

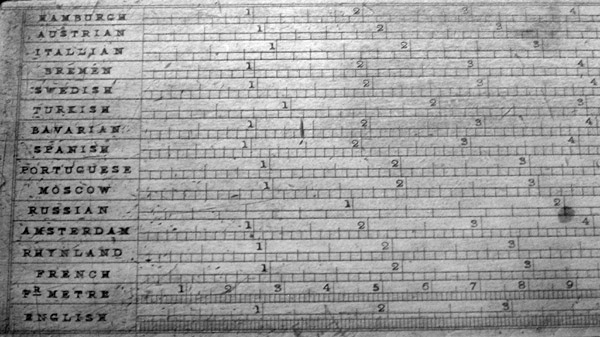

Well, the problem is, there is really no such thing as “an inch.” Why do we think that an inch exists?—well, therein lies the tale. The Wikipedia entry for “the inch” has an enlightening “inch converter” which was used before the age of the metric system. Here is the illustration:

19th Century Inch Converter — Wikipedia Commons

One can see that “the inch” has many different lengths in the 19th century. Many of them are considerably different in length. Note the Moscow and Russian inch are not even close to one another. Here’s what I have surmised from this converter about inches:

- Hamburgh – Inch divided into 8 parts. 1 inch ≈ 23.2 mm

- Austrian – Inch divided into 8 parts. 1 inch ≈ 25.8 mm

- Itallian – Inch divided into 8 parts. 1 inch ≈ 28.3 mm

- Bremen – Inch divided into 10 parts. 1 inch ≈ 23.7 mm

- Swedish – Inch divided into 12 parts. 1 inch ≈ 24.3 mm

- Turkish – Inch divided into 12 parts. 1 inch ≈ 31.3 mm

- Bavarian – Inch divided into 12 parts. 1 inch ≈ 24.0 mm

- Spanish – Inch divided into 12 parts. 1 inch ≈ 23.0 mm

- Portuguese – Inch divided into 12 parts. 1 inch ≈ 27.0 mm

- Moscow – Inch divided into 12 parts. 1 inch ≈ 27.7 mm

- Russian – Inch divided into 8 parts. 1 inch ≈ 44.1 mm

- Amsterdam – Inch divided into 12 parts. 1 inch ≈ 23.5 mm

- Rhynland – Inch divided into 12 parts. 1 inch ≈ 26.1 mm

- French – Inch divided into 12 parts. 1 inch ≈ 27.0 mm

- Fr. Metre – Centimetres divided into millimetres

- English – Inch divided into 32 parts. 1 inch ≈ 25.3 mm

Originally the Anglo-Saxons used their smallest standard, the barleycorn, to define the inch. We still use barleycorns to define shoe sizes in the US. The standard was three barleycorns in a row make an inch. I call this “The Barleycorn Inch.” The barleycorn is also called the grain. There are 7000 grains to a pound. In the 20th century, the British and Americans decided to define their inch as exactly 25.4 mm. It is sometimes called the “Industrial Inch.” This is what Americans call “The Inch.” This inch was decimalized in many industrial applications and is found on many, many US technical drawings. The decimalization of the inch is the basis for our machine tools, yet finding a ruler in the US with decimalized inches is almost impossible. Our educational system doesn’t even teach decimalized inch units and how they are used by industry. The fascination with fractions in this country is beyond my understanding.

I have converted my engineering work to be entirely metric, which can cause heartburn for some American vendors. Recently I finished a PCB design for a broadband microwave device. I sent a PCB fabricator gerber files and metric drawings of the device to be fabricated. They requested I give them drawings with dimensions in inches—I demurred. They asked again—again I told them no. Their third email to me pointed out that inches were what their equipment was calibrated to, and what they are trained to use, are used in the US, and they wanted inches.

The PCB files I sent actually were in inches as forced by US industry, but the drawings were not–so why was the vendor so insistent that I provide inch drawings? Well, in Engineering, engineering drawings define the controlling dimension. The controlling dimension is the one to which the manufacturer is expected to conform. If I have a 100 mm drawing dimension, that is what the length is supposed to be, with a tolerance in mm, not 3.937 inches and a tolerance in mils. The conversion from inch to mm is exact, the conversion from mm to inches is inexact. The vendor did not want to be held to the accuracy required in mm when they had inches on their fabrication equipment.

The point I made to them is that the controlling dimension on all engineering drawings in the US is actually metric. This is because we use the Industrial inch in the US. The definition of the US inch is 25.4 mm exactly. All the “inches” of the vendor’s equipment are calibrated and controlled by the meter, so the controlling dimension of all US drawings in inches, is actually in terms of mm (i.e. meters), we just don’t acknowledge this. The situation ended up resolving itself, and the boards were successfully fabricated. As a country we pretend that we use something called “the inch,” but it is derived from a metric standard. We use metric as our base standard, but do not adopt the convenience of the actual metric system, preferring to pretend we have “our own American/Standard” system. This is delusional.

The power the inch has over US citizens and others appears to have caused early users of metric to impose vacuous imperial conventions on the metric system. You will note that on the “inch converter” from Wikipedia the centimeter also appears in the list. As I have explained in detail in other blogs, the centimeter impedes the ease of use and soils the elegance the metric system offers. The use of millimeters only, allows for a simple and accurate implementation of metric—often without decimal points. This is experienced by Australian construction workers every day. The fact that Roy Underhill doesn’t understand the power of using millimeters, and slavishly uses centimeters instead, makes him less than a legend to me. He simply embraces folklore. The centimeter is the perfect example of an unnecessary division which appears to exist only to preserve an unnecessary and ill-defined unit of magnitude called “the inch.”. The centimeter is but a pseudo-inch, demanded by tradition and not by necessity. Its utility has proven to be non-existant in practice. Remember friends don’t let friends use centimeters. And The inch?—the definite article?—well, it’s much like fairies, and other mythical creatures, it only exists in our imagination.

Updated 2013-01-31

Related essays:

If you liked this essay and wish to support the work of The Metric Maven, please visit his Patreon Page and contribute. Also purchase his books about the metric system:

The first book is titled: Our Crumbling Invisible Infrastructure. It is a succinct set of essays that explain why the absence of the metric system in the US is detrimental to our personal heath and our economy. These essays are separately available for free on my website, but the book has them all in one place in print. The book may be purchased from Amazon here.

The second book is titled The Dimensions of the Cosmos. It takes the metric prefixes from yotta to Yocto and uses each metric prefix to describe a metric world. The book has a considerable number of color images to compliment the prose. It has been receiving good reviews. I think would be a great reference for US science teachers. It has a considerable number of scientific factoids and anecdotes that I believe would be of considerable educational use. It is available from Amazon here.

The third book is not of direct importance to metric education. It is called Death By A Thousand Cuts, A Secret History of the Metric System in The United States. This monograph explains how we have been unable to legally deal with weights and measures in the United States from George Washington, to our current day. This book is also available on Amazon here.